Adult

The upperparts (back, scapulars, centre of the rump, upperwing coverts) are dark blackish-brown, contrasting slightly with the blacker flight feathers. The sides of the rump and long uppertail and undertail coverts are white, almost completely concealing the short, black tail. The breast and belly are dark blackish-brown, with dark brown extending onto the white sides and flanks as a series irregular bars. The head, neck, upper portion of the mantle, and uppermost breast are black, sharply demarcated but contrasting only slightly with the dark brown underparts; there is a series of short, diagonally white streaks around the top of the neck forming a ‘necklace’. The iris is dark, the relatively short, stubby bill is black, and the legs and feet are black.

Juvenile

This plumage is held until late fall (November) of the first year. Juvenal-plumaged birds are similar to adults, but have fine pale terminal bars on the upperpart feathers (giving the upperparts a finely barred appearance, especially on the upperwing coverts) and there is usually no white ‘necklace’ on the completely black head and neck. In addition, the breast, belly, sides, and flanks are wholly dark sooty-grey and lack the bold white area along the sides and flanks.

Measurements

Total Length: 62.5-64 cm

Mass: 1,000-1,800 g

Source: Reed et al. (1998); Sibley (2000)

Photograph

© Tim Zurowski (Photo ID #8753)

Species Information

Biology

|

Habitat

|

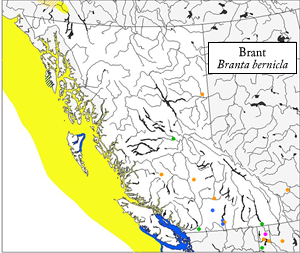

Distribution

|

Conservation

|

Taxonomy

|

Status Information

|

BC Ministry of Environment: BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer--the authoritative source for conservation information in British Columbia. |