Adult

Upperparts plain brown, sometimes with a faint olive tinge. The pointed wings show extensive rufous throughout the primaries and outer secondaries that is visible both in flight and when perched. The long, graduated tail is plain brown or olive-brown on the upperside of the central tail feathers; the remaining tail feathers are blackish with large, bold white tips (visible in flight, from below when perched, or when the tail is spread). The underparts are uniformly whitish, sometimes with a faint buff wash on the belly and undertail coverts. The underwing coverts are whitish or buffy-white. The crown, forehead, ear coverts, and nape are plain brown or grey-brown, similar in colour to the upperparts, and contrast sharply with the whitish chin and throat; the lores and area around the eye are darker dusky-grey or dusky-brown and form a slight mask. The iris is dark, the orbital ring is yellow, the slender, decurved bill is yellow with a blackish culmen, and the legs and feet are dark grey.

Juvenile

This plumage is held into the first fall but is lost through the first winter. It is similar to the adult plumage, but the outer tail feathers are greyer and with more diffuse, less well-defined, greyish-white spots at the tips of the feathers and extending up along the shaft. In addition, juvenal plumage averages somewhat duller than that of the adult, with a stronger buff wash on the throat and breast. Very young juveniles (June-August) have a largely greyish bill and orbital ring, but by late summer the bare part colouration becomes similar to that of the adult.

Measurements

Total Length: 30-31 cm

Mass: 52-77 g

Source: Hughes (1999); Sibley (2000)

Coccyzus americanus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Yellow-Billed Cuckoo

Family: Cuculidae

Species account author: Jamie Fenneman

Yellow-Billed Cuckoo

Family: Cuculidae

Species account author: Jamie Fenneman

Species Information

Biology

|

Habitat

|

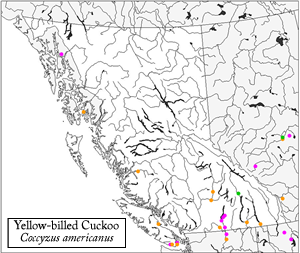

Distribution

|

Conservation

|

Taxonomy

|

Status Information

|

BC Ministry of Environment: BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer--the authoritative source for conservation information in British Columbia. |