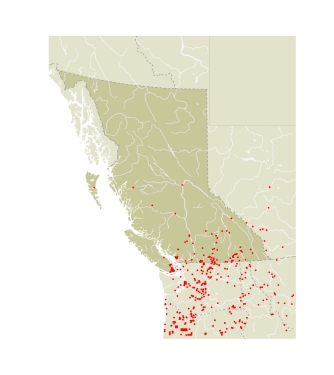

California Tortoiseshells are migratory, and migrate into BC in spring (Coles 1948). In years when large numbers migrate into BC, the larval foodplant, Ceanothus sp., can be completely defoliated over large areas. This occurred in the Kootenays in 1912, and in Lillooet and Kaslo in 1918 (Middleton 1913; Ross 1913; Cockle 1920; Anderson 1923). California Tortoiseshells hibernate in BC in piles of lumber, woodpiles, and cool buildings (Ross 1913; Cockle 1920; Hardy 1947; Downes 1948), with adults emerging in the spring (Hardy 1961, 1962b). The species is very rare or absent from BC in many years, suggesting that winter survival is very low in some years and that migrants from the south may be required to maintain BC populations. In California they migrate north and east in May and June, and south and west in September and October (Shapiro 1976c). The adults have been seen migrating up mountains in California in midsummer, possibly in search of larval foodplants (Tilden 1962).

Larvae feed on Ceanothus species, usually C. sanguineus, in BC (Harvey 1908; Cockle 1920; Dyar 1904b; FIS; CSG). California Tortoiseshells found in coastal BC tend to be larger and paler than those in the interior. The coastal BC California Tortoiseshells are all migrants, and they cannot successfully breed there because their larval foodplant occurs only in very small, isolated populations on the coast. California Tortoiseshells successfully produce one new generation in the summer in the interior, and those butterflies are smaller and darker than the coastal ones. This is the phenotype that was named subspecies herri in Colorado.

Exudations from freshly opening young needles of true firs, Abies, are a major food source for adults in California (Wright 1891) and the butterflies feed on fir sap on Vancouver Island in October (Danby 1891). They also mud-puddle and feed on overripe fruit such as blackberries and apples (Hardy 1961). Spring migrants use early spring flowering bulbs such as crocuses as nectar sources (CSG).

|

|