The North American Badger (Taxidea taxus) is among one of the largest members of the weasel family. As mid-sized semifossorial carnivores, they are adapted for digging to obtain food and shelter. Characteristic white and black facial markings include black cheek patches, often referred to as “badges”, and a narrow white stripe that runs from nose to shoulder. Short rounded ears on the side of the badger’s head have stiff hair bristles, which deflect soil away from their openings. The forelimbs and chest are broad and muscled for digging. Long, robust front claws ably dig into hardened soil, while their back feet feature short spoon-like claws used to throw loose soil to the rear. Both front and rear toes are partially webbed for strength and digging efficiency; this webbing, in part, also makes badgers good swimmers.

The top and sides of the body consist of coarse, gray-yellow fur, and varying shades of cream, tan, or white fur cover the underside. The lower legs and feet are black. Long guard hairs on the back and sides, along with a stout and broad neck and body, give the body a flattened appearance. The head is conical and wedge-shaped for thrusting into small animal burrows. Adult badgers in BC usually range in length from 72 to 91 cm, including the short bushy triangular tail, which is typically 10 to 14 cm long. Adult females weigh between 6 and 9 kg, while larger adult males weigh between 9 and 13 kg.

American Badger; Badger

Family: Mustelidae

Introduction

|

Species Information

Biology

|

Habitat

|

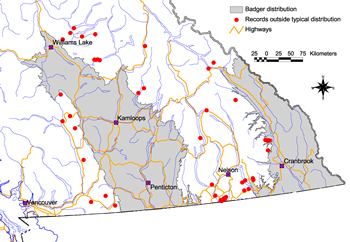

Distribution

|

Taxonomy

|

Comments

|

Status Information

BC Ministry of Environment: BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer--the authoritative source for conservation information in British Columbia. |

Taxonomic and Nomenclatural Links

Additional Range and Status Information Links

Additional Photo Sources

Species References

|

Apps, C. D., N. J. Newhouse, and T. A. Kinley. 2002. Habitat associations of American badgers in southeastern British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Zoology 80:1228-1239. British Columbia Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. 2004. Badger (Taxidea taxus jeffersonii) Species Accounts In: Accounts and Measures for Managing Identified Wildlife. British Columbia Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, Victoria. Hoodicoff, C. S. 2003. Ecology of the badger (Taxidea taxus jeffersonii in the Thompson region of British Columbia: Implications for conservation. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. jeffersonii Badger Recovery Team. 2008. Recovery Strategy for the Badger (Taxidea taxus) in British Columbia. Ministry of Environment, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. Kinley, T. A., and N. J. Newhouse. 2008. Ecology and translocation-aided recovery of an endangered badger population. Journal of Wildlife Management 72:113-122. Kyle, C. J., R. D. Weir, N. J. Newhouse, H. Davis, and C. Strobeck. 2004. Genetic structure of sensitive and endangered northwestern badger populations (Taxidea taxus taxus and T.t. jeffersonii. Journal of Mammalogy 85:633-639. Long, C., and C. Killingley. 1983. The Badgers of the World. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. Michener, G. 2000. Caching of Richardson's ground squirrels by North American badgers. Journal of Mammalogy 81:1106-1117.

Weir, R. D., H. Davis, and D. V. Gayton. 2004. Survey of badger burrow damage to machinery and livestock. Artemis Wildlife Consultants, Armstrong, British Columbia and FORREX, Nelson, British Columbia, Canada. Prepared for BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. |