In British Columbia, this species can be distinguished from the much more common Western Kingbird by its shallowly notched or forked tail that lacks any white in the outer tail feathers (Western Kingbird, in contrast, has a square-tipped tail with white outer webs to the outermost feathers). In addition, Western Kingbird has a pale grey head (palest on the throat) and greenish-grey upperparts, whereas Tropical Kingbird has a relatively darker grey head with darker ear coverts (giving the suggestion of a dark ‘mask’) and greener upperparts. The upper breast of Tropical Kingbird is variably tinged with green, whereas in Western Kingbird there is a relatively sharp demarcation between the yellow underparts and grey upper breast. The bill of Tropical Kingbird is also noticeably longer and heavier than that of the Western Kingbird.

Although it has never been recorded as a vagrant in British Columbia, Couch’s Kingbird of southern Texas, Mexico, and Central America could potentially wander north and should be considered when identifying potential Tropical Kingbirds, particularly those that occur in the interior or at seasons outside of the fall and early winter. This species is extremely similar to Tropical Kingbird and is best identified by voice. Tropical Kingbird gives a rapid, sputtering twitter that is very different from the high, thin, nasal squeals: (towi towi toWITItoo) of Couch’s Kingbird that often include single notes (single notes never included in the calls of Tropical Kingbirds). Other subtle morphological differences between the two species include the slighter shorter, heavier bill of Couch’s Kingbird as well as the more evenly-spaced primary tips of males (primary tips of male Tropical Kingbird uneven and staggered). Another potential confusion species that has not yet occurred in British Columbia, Cassin’s Kingbird, is somewhat similar to Western Kingbird and is distinguished from Tropical Kingbird by its darker grey head, breast, and upperparts with strongly contrasting whitish throat and malar area, as well as its square-tipped tail with a narrow pale terminal band.

Source: Wood (2006)

| The commonly-heard call in British Columbia is a high, sputtering twitter of sharp, metallic notes: tzitzitzitzitzitzitzi or trililililililil. Source:Stouffer and Chesser (1998) |

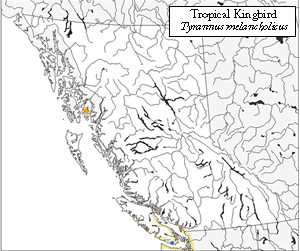

This species is a non-breeding wanderer to British Columbia.

|

The Tropical Kingbird feeds almost exclusively on insects, although it also consumes some berries and small fruits during the non-breeding season; some birds in British Columbia have been observed eating berries, particularly during November. Most insects are captured in the air, although it occasionally gleans prey from the branches or foliage of nearby vegetation or, rarely, lands and picks prey from the ground. Birds in B.C. have been observed foraging on flies and other insects on and around piles of kelp that have washed up on beaches. Flying insects are captured during bouts of ‘flycatching’ or ‘hawking’, in which the species will perch for prolonged periods visually searching for nearby flying insects, then dart out into the air to capture its prey and subsequently return to the same or a nearby perch. Most prey is consumed in the air, although large insects are often brought back to the perch and consumed there.

Source: Stouffer and Chesser (1998)

|

|