Mating is thought to take place in autumn and winter. Fertilization occurs in spring after departure from the hibernaculum. Males may attain sexual maturity in their first year; females may breed in their first year but many do not breed until their second. Although twins are typical in eastern North America, single young are usually produced in the west. The scanty data available for the province suggest that the young are born in late June. Nevertheless, birth dates and development of the young can be extremely variable, differing among roosts and even among individuals within a roost. Pregnant females, females with newborn young and females with well-developed young can be found together in the same roost. In the Okanagan, considerable year-to-year variation has been observed, with dates for the first appearance of the young varying as much as a month. This variation probably results from year to year differences in climate. Newborn young weigh about three grams. They are naked and blind although the eyes open within a few hours after birth. Juveniles are capable of flying at 18 to 35 days of age. There are longevity records showing that this species can live at least 19 years in the wild.

|

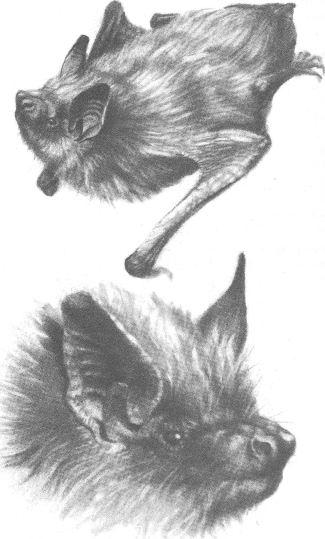

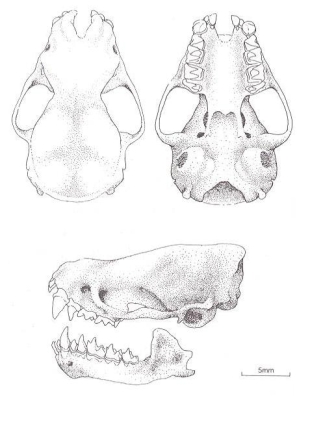

This species emerges around dusk to feed. It is regarded as a generalist that hunts in a variety of situations: over water, over forest canopies, along roads, in clearings, and in urban areas, often around street lights that attract insects. The intensity of its echolocation calls is very high. In open areas such as forest clearings and over water the Big Brown Bat may first detect prey as far as 5 metres away. In most locations beetles are an important part of the diet and the heavy teeth and strong jaws of this bat appear to be an adaptation for chewing hard-shelled insects. Nevertheless, remains of moths, termites, carpenter ants, lacewings and various flies also have been identified in faecal pellets.

The only data on feeding biology for the province comes from research undertaken at Okanagan Falls. There the Big Brown Bat emerges 30 to 40 minutes after sunset and hunts 5 to 10 metres above the water along a 300-metre stretch of river. It is a relatively fast flyer, able to attain a speed of 4 metres per second when pursuing prey. The Big Brown Bat makes several feeding flights during the night, each 30 to 60 minutes in duration. Between flights it usually roosts near the feeding area. During the day it roosts as far as 4 kilometres from the feeding area, even though there are sites near the Okanagan River suitable for day roosts.

Large caddisflies are the major prey at Okanagan Falls. Midges are the dominant insect group in the area, but the Big Brown Bat does not eat them. The echolocation calls of this bat should enable it to detect midges at a distance of about a metre. Either it is unable to react quickly enough to capture them or it simply prefers larger prey.

|

Throughout its range this bat demonstrates a strong affinity for buildings and it is often referred to as a house bat or barn bat. In British Columbia, maternity colonies have been found in the attics of houses, cabins and barns. But in the Okanagan Valley this species rarely roosts in man-made structures; there, maternity colonies have been found in cavities in dead Ponderosa Pines and rock crevices.

The Big Brown Bat is less tolerant of high temperatures than other species that use attics such as the Little Brown Myotis and Yuma Myotis. Temperatures above 35°C will often force the Big Brown Bat to move to a cooler site within the roost or change roosts altogether. Maternity colonies as large as 700 individuals have been reported, but those associated with buildings in British Columbia are small, comprising no more than 50. The tree colonies studied in the Okanagan contain any number from a few to 200 bats, with an average of about 100. Loyalty to roosting sites seems to depend on the type of roost. Big Brown Bats roosting in buildings or rock crevices show a strong fidelity to those sites; however, those roosting in trees seem to move regularly between several established roosts. Some recent genetic research has revealed that most individuals in maternity colonies are closely related.

This species' hibernation period varies with local climate and geography. In the interior of the province, it lasts from November to April. In British Columbia's southern regions, the Big Brown Bat may be active for short periods in winter. Migrations of almost 300 kilometres have been documented, but most individuals travel no more than 80 kilometres between summer and winter roosts. Populations exploiting buildings may even use the same site in winter and summer. (Despite its rather sedentary nature, experiments have demonstrated that this species possesses a remarkable homing ability: individuals released 400 kilometres from their roosts managed to find their way back.)

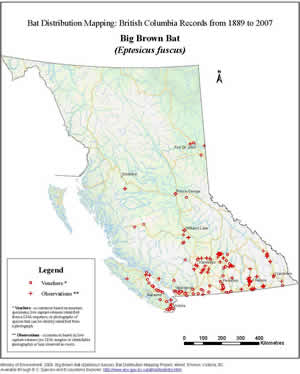

The Big Brown Bat hibernates in buildings, caves and mines; in western Canada most populations appear to use buildings. Hibernating colonies are typically small, although large colonies have been found in a few caves and mines in eastern North America. As with most of our bats, information on winter biology in British Columbia is sketchy and derived largely from incidental information on museum specimens. There are coastal winter records from Victoria and interior records from as far north as Williams Lake and Prince George. Most of these winter records are from buildings; this mammal is rarely found in caves or mines in the province.

In eastern Canada, swarming behaviour often takes place at mines and caves before this species enters hibernation. The Big Brown Bat hibernates alone or in clusters of as many as 100. This is a hardy bat capable of withstanding low temperatures. It selects a dry microenvironment with temperatures of -10 to -5°C, although temperatures below -4°C will usually stimulate arousal. When the Big Brown Bat enters hibernation in late autumn it weighs about 25 grams; when it completes hibernation in spring it weighs about 19 grams, having lost about 25% of its body weight. In caves or mines it hibernates in exposed areas near the entrance where it hangs from the ceiling and walls, or it wedges itself into small crevices or under rocks. Big Brown Bats often arouse from hibernation to change roosting locations; there are several observations of this bat outside on the walls of buildings when temperatures were well below freezing. There is some evidence that winter activity is more common in buildings where conditions for hibernation may not be ideal.

|

|