PROTOCOLS FOR RARE PLANT SURVEYS

(Red- and Blue-listed Species)

Deltoid Balsamroot (Balsamorhiza deltoidea), photo by Roman Stone.

by

Jenifer Penny and Rose Klinkenberg

(British Columbia Conservation Data Centre and E-Flora BC)

INTRODUCTION

The BC Species and Ecosystem Explorer shows that British Columbia is home to 3190 native vascular plant taxa. It also lists 890 species of mosses found in BC and 580 species of macrolichens (microlichens are not yet covered). Current status assessments/listings are provided for these species.

Surveying for rare species in these species groups requires a specialized knowledge-base. In recognition of the need for appropriate methods and expertise in rare plant survey work, we have prepared the following guidelines and general information on rare plant work.

WHICH SPECIES ARE RARE IN BC?

A first step in rare plant surveys is to know which species are rare in the BC flora, and which are present in our region. In British Columbia, there are two ways to obtain a list of the rare plant species of the province:

Hermann's Dwarf Rush (Juncus hemiendytus), photo by Adolf Ceska

WHO SHOULD SURVEY FOR RARE PLANTS?

Anyone can develop the skills to become a field botanist by building their knowledge base of regional species and by developing familiarity with the proper tools and methods for identifying plant species. And anyone can become a rare plant surveyor by further honing their identification skills and building their knowledge base. But both of these areas--field botany and rare plant survey work--require special sets of knowledge that include strong familiarity with plant ecology and plant taxonomy. An expert field botanist and rare plant surveyor needs to know what a species needs to grow, and thus where it might be found, and they need to know the plant communities in which it occurs.

To help guide managers in hiring the appropriate expertise for rare plant survey work, several jurisdictions have compiled guidelines for rare plant survey work.

The Washington Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) has identified the following three points as the most important factors in rare plant survey work:

The WDNR and the Alberta Native Plant Council (ANPC) have compiled guidelines for the qualifications of rare plant surveyors. These include:

See the following links for additional details on qualifications:

Protocols for Surveying and Evaluating Impacts to Special Status Native Plant Populations and Natural Communities

Oregon Ash (Fraxinus latifolia), photo by Tricia deMacedo

TOOLS FOR IDENTIFYING RARE SPECIES

Recognizing or identifying rare species in an area requires working with technical manuals--or regional floras. These manuals cover all species in the regional flora and provide taxonomic keys that aid in identification and separation of similar species using key taxonomic characters. The following manuals and sources provide technical level identification aids for BC species.

Vascular Plants:

While common field guides can be useful in getting into the ball park in species identification, serious botanical work is carried out using regional floras. Regional floras outline all possible species that can be found in a region and generally provide identification keys and illustrations.

In BC, the regional flora for vascular plants is The Illustrated Flora of British Columbia, an 8-volume series that covers all vascular species in the province up to 2002. Much of this flora is available online on E-Flora BC. Keys continue to be added.

The Flora of the Pacific Northwest is also an important reference manual.

For species discovered or added to the flora since the publication of the Illustrated Flora, check the E-Flora BC listings and atlas pages, and the BC Species and Ecosystem Explorer. In E-Flora, species added to the flora since 2002 are shown in our search pages with yellow buttons which indicates that they do not yet have full descriptions available. However, these descriptions are often available in other publications and floras from other regions, and links are provided.

Non-vascular Plants:

For non-vascular plants, resources include

Short-rayed aster (Symphyotrichum frondosum), photo by Brian Klinkenberg

THE ROLE OF THE HERBARIUM IN RARE PLANT WORK

Rare plant work means spending a lot of time in a herbarium, both prior to field work and after field work when voucher specimen identification and verification is needed. Collections are used to become familiar with all species in a group, and to check identifications. It is through comparison with other collections of the species, and other collections of similar species, that a solid identification is made. All valid botanical work is specimen-based. Rare plant surveys should build in time for specimen collection and processing in order to ensure accuracy of records.

The expertise needed to identify or verify the identity of a rare plant species will vary from group to group and you may require additional expertise to confirm a record. To determine who the appropriate expert is for a given plant group, check the published literature and the local floras to see who has either studied the group taxonomically, or who has worked intensively with the group during survey work. Often, herbarium staff will assist with identification or verification, usually for a fee that goes towards herbarium costs. Presently, the UBC Herbarium, for example, provides assistance with plant identification, and they can also provide direction on where to obtain needed expertise for difficult groups.

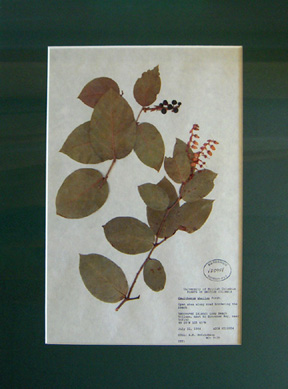

A UBC Herbarium specimen of Salal. A voucher specimen should show as many parts as

possible, from flowers and fruits to leaves, stems, and when needed, roots.

View a close up of a plant collection

VOUCHER SPECIMENS

In British Columbia, the province of BC has outlined key requirements for species identification and confirmation, and the scientific importance of voucher specimens (Province of BC 1996), as follows:

"Because the accuracy of identifications may require re-examination of specimens, and because species names are not static and may be revised as new species are discovered or existing ones are split or lumped, it is imperative that voucher specimens be prepared when species inventories are being compiled. Voucher specimens are a series of specimens of each species [observed] during a study. Each series is labeled as vouchers and deposited in, preferably, a recognized biosystematic collection for future reference."

"The importance of voucher specimens is evident in the following hypothetical example. If your species A is later determined to consist of three species, A, B, and C, a series of specimens from your study must be examined to determine which of these species were actually represented in your study. In addition, if the newly named species B is discovered to be among your voucher specimens, but it is no longer found in the area you surveyed, you may reasonably conclude that it has been extirpated. Without the voucher specimens this important change in species status might be overlooked."

COLLECTON GUIDELINES FOR RARE SPECIES

All field botanists eventually come up against the dilemma of when to collect vouchers for rare plant species. Although there is no single rule to guide this, many botanists follow a general rule of thumb (read the Botanical Electronic News article on this rule of thumb).

Vouchers are very critical in rare plant work, but rare plant populations can often be very small, making voucher collections questionable. The surveyor has to weigh the pros and cons of taking specimens in these cases.

Full vouchers (entire plants) should only be taken if the population is large enough to withstand the loss of an individual, or if the rare species is locally abundant. Use the general rule of thumb. However, this number must be assessed on a species by species basis, and there really is no substitute for a specimen to verify species identification.

Clonal plants and tufted plants can usually withstand collection of part of a plant or entire stems.

Although some rare species are reported to be sensitive to the genetic loss of even one individual, and this loss can precipitate population declines, most species can usually withstand collection of a partial specimen.

If you are uncertain about the impact of taking a full collection, then vouchers should consist of only a partial specimen, such as a flowering branch, and should include associated photo documentation. All collections of even partial specimens should consider the impact on recruitment of loss of flowers and seeds. There is growing evidence that small losses of recruitment in some rare plant populations can lead to population decline.

Some species can be vouchered with photographs. This would apply for very distinctive species where no confusion about species identity can occur.

Contact us if you have any questions about vouchering your plant finds.

Hooker's Townsendia (Townsendia hookeri), photo by Jamie Fenneman

METHODOLOGIES FOR RARE PLANT SURVEY WORK

In conducting surveys for rare plants, it is important to recognize that methods used for vegetation surveys do not directly apply. Rare plant species are sparsely distributed in the landscape, appearing infrequently and often in specialized habitats. Instead, floristic survey procedures are used.

In vegetation surveys, study sites are generally approached in a systematic way using sampling grids or transects to ensure coverage of the site variation. The aim of the work is to sample representatives of the plant community types present, using sampling theory to determine effective sampling percentages of a site. Sampling work is often done only once in a growing season.

In floristic survey work, there are some important differences. During specific site assessments, floristic survey work is aimed at detecting rare and significant plant species within the survey area, and thus requires complete site coverage of suitable habitat throughout the growing season. Transects or grids may still be used to ensure site coverage and allowing mapping of rare species, however, the aim is not to "sample", but to survey the entire site.

For targeted rare plant surveys, where a single species is being sought (e.g. for status report work), site survey will be focused only on suitable habitat within a site, or within a region. The key habitat types will be identified ahead of time and then thoroughly searched during field work. When targeting a single species, survey work should be undertaken during the flowering period in order to maximize the likelihood of detection. This is particularly important for species that are obscure when not in flower, but also aids in searching for more showy plants and can reduce the amount of time spent surveying.

One important difference between vegetation and floristic surveys is the need for seasonal coverage in order to best detect rare species occurrences. While many rare species, though not all, can be found throughout the growing season by a knowledgeable botanist familiar with the flora, seasonal coverage that targets flowering periods will increase the accuracy of the survey and the likelihood of detecting species that would otherwise be difficult to spot. Detection is probably the most important component of rare plant survey work. Flowering plant species are more easily noticed during their flowering period, with a reduction in detection once flowering is past. Ideally, a site will be surveyed during the following periods: early spring, later spring, early summer, later summer, early fall. This type of coverage will capture the flowering periods of most species, including spring ephemerals that completely disappear after flowering.

In addition to seasonal coverage, surveying in more than one year is also important for rare plant survey work. If this is possible, it improves the likelihood of spotting some species. There are plant communities, such as shoreline wetland communities, where the composition and abundance of species can change from year to year because of annual climatic variation and resulting water level fluctuation. Water levels influence germination in annual wetland species. The same 'climatic' effect is can be seen in other ecosystem types. Plant abundances and presence can vary from year to year depending on annual variation in precipitation and temperature. Detection of rare species will be greater if more than one year of survey is carried out.

Floristic survey work also requires an assessment of plant community and habitat types present in a site, thus drawing upon the plant ecology knowledge of the surveyor. While rare species can occur in a broad range of communities and habitats, they often occur more frequently in some habitats or communities. For example, areas of limestone outcrops are well-known to support a high percentage of rare species. This assessment of habitat and community types requires a degree of knowledge on the part of the surveyor that allows for targeting of specialized habitats, or habitat types where rare species occurrences are most likely. This type of floristic assessments requires a good familiarity with the flora and with habitat types and associations with rare species.

Read about the coincidence of rare plants and landform types.

Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae), photo by Mike Edley

GENERAL STEPS FOR FLORISTIC SITE SURVEYS

1) Obtain and review all available mapping for the study area or region, including site maps, topographic maps, species mapping, etc.;

2) Determine the habitat and ecosystems present in the study area;

3) Obtain and review a list of the species possibly present in the study area. Review the regional status for these species and highlight the rare species of the region;

4) Compare the list of regional rare species with available habitat types in the study area;

5) Review the flowering periods and growing requirements for rare species that maybe encountered in order to determine survey periods;

6) Flag habitat types within the study area that are high priority for searching;

7) Ensure seasonal coverage of the site in order to embrace flowering periods;

8) Obtain voucher documentation for each rare species found;

9) Check identifications with experts using herbarium collections, and obtain verifications of identifications.

Alkali Plantain (Plantago eriopoda), photo by Jamie Fenneman

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READING

Alberta Native Plant Council. 2000 ANPC Guidelines for Rare Plant Surveys in Alberta. Web citation: Available http://www.anpc.ab.ca/assets/rareplant.pdf

Douglas, George. W., Del Meidinger and Jenifer L. Penny. 2002. Rare Native Vascular Plants of British Columbia. Province of British Columbia, Victoria.

Douglas, G.W., D.V. Meidinger and J. Pojar (editors). 2002. Illustrated Flora of British Columbia, Volume 8: General Summary, Maps and Keys. B.C. Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management and B.C. Ministry of Forests. Victoria. 457 p.

Klinkenberg, B. 1997. Hot Spots: a spatial-temporal analysis of the rare vascular plants in the Carolinian Counties of southwestern Ontario. Report submitted to the World Wildlife Fund (Canada). 56 pages.

Klinkenberg, Brian. 2002. Spatial analysis of the coincidence of rare vascular plants in the Carolinian Zone of Canada: implications for protection. Canadian Geographer. 46 (3):194-203.

Klinkenberg, B. and R. Klinkenberg. 2002. Biodiversity Protection: Inventory and Monitoring Standards for Rare Rhizomatous Geophytes in British Columbia. Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management, Victoria.

Native Plant Society of Saskatchewan. 1998. Guidelines for Rare Plant Surveys.

Province of British Columbia. 1996. Directory of Experts in the Identification of British Columbia Species. Ministry of Forests Research Program, Victoria.

Washington Department of Natural Resources. 2006. Suggested guidelines for conducting Rare Plant Surveys for Environmental Review. Washington Department of Natural Resources. Available online.

Recommended citation: Author, date, page title. In: Klinkenberg, Brian. (Editor) 2023. E-Flora BC: Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia [eflora.bc.ca]. Lab for Advanced Spatial Analysis, Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. [Date Accessed]

E-Flora BC: An initiative of the Spatial Data Lab, Department of Geography UBC, and the UBC Herbarium.

© Copyright 2023 E-Flora BC.